Innovation fit for the Queen – Aerogard born in Canberra and WW II

The innovation that kept flies off Queen Elizabeth on a golf day in Canberra in 1963 became Australia’s iconic insect repellent – Aerogard – just one of the amazing results born out of 91 years of CSIRO in the national capital.

At a garden party at Canberra’s Government House in 1963, Queen Elizabeth was left madly swatting away flies after one of her aides lost the nerve to spray Her Majesty with a repellent developed by CSIRO’s famous entomologist Doug Waterhouse.

Above: Fighting mosquito threats.

Learning from experience, the next day was a different story – as documented in CSIROpedia:

“… Government House staff made sure the Queen was liberally sprayed before heading off for a game of golf. Journalists following the Queen noted the absence of flies around the official party and word about CSIRO’s new fly-repellent spread.”

Above: Doug Waterhouse.

“A few days later the good people at Mortein called Doug Waterhouse for his formula, which he passed on freely, as was CSIRO’s policy at the time. The rest, as they say, is history with Mortein’s Aerogard going on to become an Australian icon, ensuring that we all ‘avagoodweekend’.”

After being recruited to the then CSIR Division of Economic Entomology, in Canberra in 1938, Doug carried out pioneering research to tackle Australia’s sheep blowfly problem. This research was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

Above: Aerogard.

Commissioned with the rank of Captain in the Army Medical Corps, Doug was located in the Officer Reserves in Canberra and could be transferred to active service as needed. This arrangement gave flexibility for his wartime research focussed on finding ways to prevent malarial transmission by mosquitos. Speaking in 1993 about his work, Doug said:

“To begin with, I was testing oils for spraying onto mosquito breeding grounds … I also had to test materials which might be used for mosquito sprays and housefly sprays to stop transmission of diseases.”

“For my tests, I would sit in a large muslin cage in a room, along with a thousand or so mosquitoes, and have a substance on each leg, another one on an arm and so on. This work got into the press, and as a result, we got many letters suggesting all sorts of materials and mixtures to be tested. As a matter of course, I tested all of these and all of their ingredients.”

Above: No flies on Queen Elizabeth at barbecue at Government House (1970). Source: National Archive of Australia.

Following some feedback from an oil company, Doug started testing a range of phthalates.

“I found that the diluted dimethyl phthalate was a good repellent but the pure dimethyl phthalate was quite outstanding.”

The formula was found to be equally as effective in field conditions in Newcastle and Cairns and with malarial mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Rather than experimenting on troops, Doug tested the product on himself and results were confirmed by entomological colleagues and given the go-ahead for use in the war.

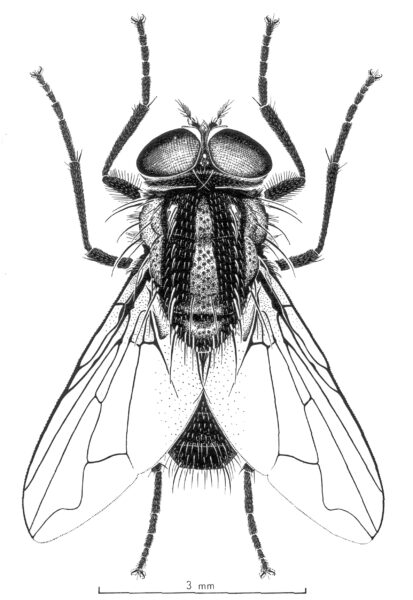

Above: The Australian Bush Fly Musca vetustissima.

By 1943 the repellent, known as ‘Mary’, was protecting Allied troops throughout the Pacific from malarial mosquitoes. Doug and CSIRO were unsung war heroes and this all gave rise to saving the Queen from the annoyance of Australia’s bush flies and to the ultimate development of Aerogard some 20 years later.

Above: 90 years of innovation in Canberra since the opening (here) of our Black Mountain site in 1927.

The Aerogard formula was just one of a long list of achievements credited to Doug Waterhouse during his 60 years as a renowned entomologist, scientist and administrator with CSIRO in Canberra. His contribution was pivotal to CSIRO’s successful blowfly research, to the development of integrated pest management and to CSIRO’s international recognition as a major centre for entomological research.

CSIRO has been solving some of the nation’s greatest challenges in the national capital since we opened our foundation building on Black Mountain in 1927. We like to share some of those stories on this site. And, by the way, we’re still finding ways to stop the mozzie disease threat.