Beating the heat at Ginninderra

We’ve all experienced the cool relief of seeking respite from a hot day under a shady tree. Recent studies have shown that tree cover plays a large part in combating the urban heat island effect.

Canberra is hot and getting hotter. Temperatures in the ACT have been increasing since about 1950.

Canberra sweltered though 10 consecutive days of 30-degree plus temperatures in early March, providing our hottest start to autumn on record.

This warming trend is set to continue, with recent projections of Canberra’s future climate indicating that temperatures are likely to rise further, resulting in more hot days and fewer cold nights.

This is exacerbated by the Urban Heat Island effect, where cities tend to trap and store heat during the day, staying hotter for longer than the surrounding countryside during the night.

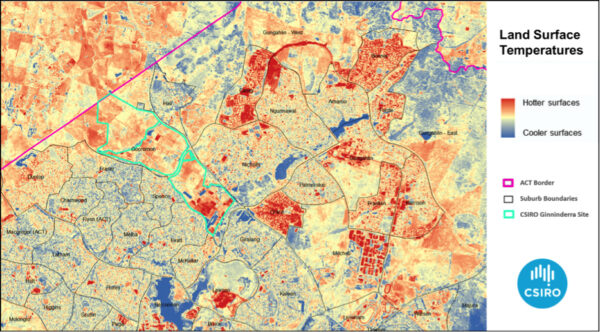

To understand patterns of urban heat across Canberra, researchers in CSIRO Land & Water have used satellite thermal imagery to estimate land surface temperatures and map their distribution.

We recently tested this at Ginninderra Field Station, which yielded some very interesting results.

Dr Matt Beaty, a Senior Experimental Scientist in CSIRO Land & Water said, “As with other cities around Australia, there is a strong relationship between vegetation and land surface temperatures.”

“Newer suburbs, and industrial areas in Canberra with little vegetation cover, are typically much hotter during summer than older suburbs with established tree cover providing dense shade.”

The availability of water is also important. Not just to support healthy vegetation, but to drive the processes of evaporation and transpiration that provide cooling benefits in addition to tree shade.

CSIRO’s urban heat mapping for Canberra has been featured by the ACT Government in their draft ACT Climate Change Adaptation Strategy which is open for public consultation until 3 April 2016.

“There is a lot to be learnt from this urban heat mapping work that is relevant to the proposed urban development of the Ginninderra site and how we adapt our cities to climate change,” said Dr Beaty.

CSIRO heat mapping for the northern part of Canberra (shown below) identifies that during a hot summer day established suburbs are cooler than the Ginninderra site and surrounding countryside.

“This is due to the influence of suburban gardens and associated irrigation, which tends to result in cooler land surfaces than bare cultivated soils and dry sheep paddocks.”

The coolest parts of the Ginninderra site are the waterways and areas with existing tree cover.

“What this means is that large trees, irrigated grass and water will need to be a key feature of the design of any potential future urban development to combat the Urban Heat Island effect through the provision of shade and to drive the cooling benefits of evapotranspiration,” Beaty said.

Based on site investigations so far, approximately 150 hectares of the land on the Ginninderra site is unable to be developed due to its topography, heritage and ecological values, and is envisaged to form an open space network of connected recreational and conservation areas. This idea of ‘fingers of green’ through the site was reflected in the draft concept presented to the community last year.

But it’s not all about trees, other strategies for adapting our cities to increasing urban heat include the use of light-coloured construction materials in our buildings and paved surfaces. Light coloured surfaces reflect incoming solar radiation, reducing the amount of heat that is trapped in our cities.

Jacqui Meyers, another Senior Experimental Scientist in CSIRO Land & Water has undertaken research on the impact of climate change on the heating and cooling energy costs of a typical Canberra home. This research is also cited in the ACT Government’s draft ACT Climate Change Adaptation Strategy.

“The energy required to heat a typical Canberra home in 2070 may be one-third lower, but energy for cooling could more than double,” Myers said.

“An integrated response to urban heat is required, which includes a focus on climate-wise buildings, planning provisions that provide space for trees to shade buildings and pedestrians, and open space networks that support healthy vegetation and waterways to deliver further cooling benefits.”

Overall, there are many opportunities for science to inform the planning and design of the proposed urban development of the Ginninderra site. More tree cover is good for addressing the urban heat island effect, but would also provide many other social and economic benefits.